Taiwan vs US Chip Subsidies – Bolstering the Sacred Mountain

How an island went from farming sugar cane to fabricating semiconductors

Taiwan’s government in the 1970s planted the seeds for the world’s most important chipmaking ecosystem.

Today, the island’s policymakers are tasked with preserving what Chinese-language commentators have dubbed Taiwan’s “Sacred Mountain of Protection” [护台神山] — its advanced semiconductor manufacturing industry.

This article covers the latest chapter of Taiwan’s semiconductor public policy, continuing Chip Capitols series of deep-dives comparing chip subsidy regimes in the United States, China, Europe, South Korea, and (soon) Japan.

Taiwan’s chip policy is as unique as its industry’s history:

Whereas policymakers in the US and South Korea direct government funds toward closing supply chain weaknesses, Taiwanese policymakers allow companies to determine which technologies to lean into.

Whereas lawmakers in the US and EU attach tight strings to the subsidies that administrative agencies dole out, Taiwanese lawmakers write vague laws that grant enormous discretion to government ministries.

And whereas local governments in mainland China steer a significant share of the nation’s total semiconductor subsidies, Taiwan’s central government funds and manages the island’s most meaningful incentive programs.

Today’s article will:

Recount the history of Taiwan’s semiconductor public policies;

Contextualize Taiwan’s current position in the global chip supply chain; and

Show how Taiwan’s modern chip subsidies reflect a centrally administered national strategy committed to bolstering existing strengths.

Why Fund Chips?

Taiwan

A Vertically Disintegrated Success Story

Originally an agrarian economy, Taiwan’s Ministry of Economic Affairs (MOEA) set the country on the path to economic property by designating the semiconductor industry as its future economic fulcrum. The Industrial Technology Research Institute (ITRI) consortium emerged as the nucleus of MOEA’s vision. Taking the reins as project manager, ITRI converted a far-reaching vision into a tangible reality.

In 1976, ITRI channeled government support to secure basic design IP, manufacturing process technology rights, and a 3-inch wafer demonstration factory. These investments laid the foundation for future semiconductor activities on the island. In addition to buying foundational IP and physical infrastructure, government authorities in 1979 persuaded prominent Taiwanese corporations like CDF, TECO, and the Taiwanese Bank of Communications to contribute to ITRI’s funding.

These endeavors helped privatize some of ITRI’s research projects, birthing the United Microelectronics Corporation (UMC) in 1980. The momentum behind establishing independent chip companies continued, culminating in the birth of TSMC in 1987. By pioneering the pure-play foundry model —focusing solely on manufacturing chips designed by other companies— TSMC secured Taiwan’s unique position in the global chip industry.

The successes of these nascent companies made it clear that Taiwan’s government could profit from investments in R&D. In 1990, the government contracted with ERSO (the Electronics Research and Service Organization, an office of ITRI) to advance manufacturing process technology for memory chips. This led to the establishment of Vanguard, a government-backed spinoff. Taxpayers soon learned they could rest easy when the initial $100 million public investment in the memory chip project quadrupled in the form of Vanguard stock within two years.

These commercial successes also led to a shift in R&D funding from being mostly government-led to industry-led. Although MOEA’s absolute contributions remained constant, its relative share of Taiwan’s total R&D spending dropped from 44% in 1990 to 6.5% by 1999.

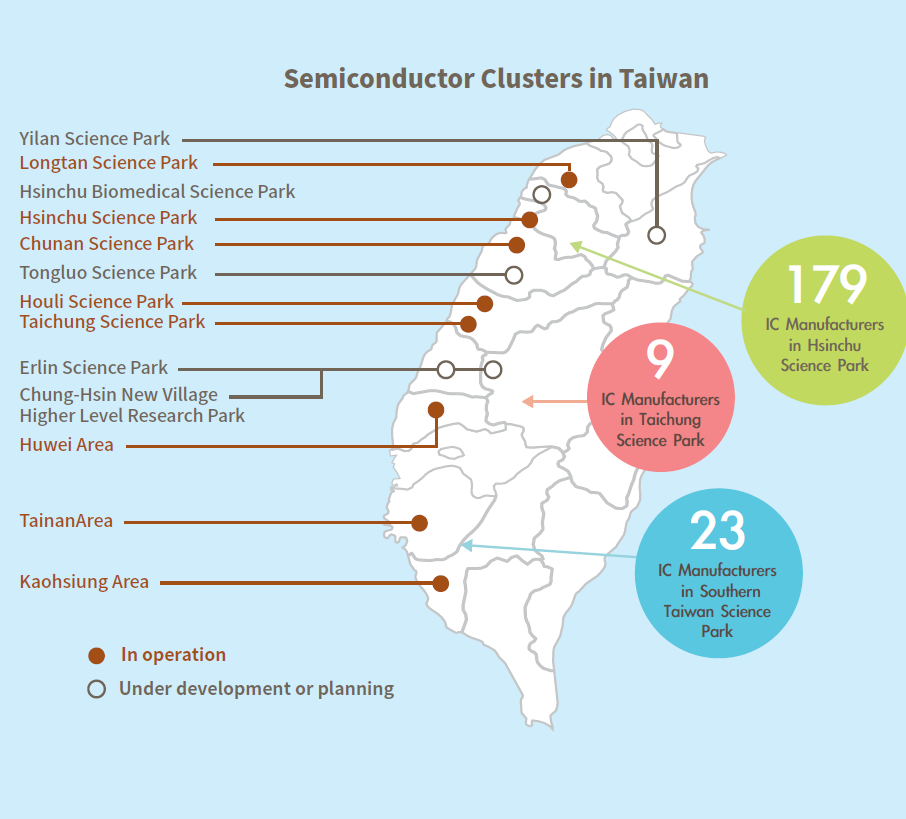

In addition to directly funding early research projects, Taiwan’s central authorities also sought to create corporate-friendly environments for later commercial success. Science parks were key to this strategy. Hsinchu Science Park, for example, attracted companies with dual-pronged tax incentives:

First, it allowed IC companies to write off investments in physical infrastructure during their initial five years of operation.

Second, it offered a tax shelter for any capital that companies planned to allocate to the IC industry.

This enclave was a collaborative effort between the government and existing chip companies. As a centrally managed entity, Hsinchu functions as an incubator for companies engaged in consumer electronics manufacturing, IC design, and related industries. The township has developed into a bustling nerve center, boasting a workforce of over 150,000 technical employees.

To cultivate the next wave of high-tech talent in these clusters, the Taiwanese government has over the past twenty years fostered partnerships between industry and academia. Since 2019, Taiwan has partnered with premier domestic academic institutions to establish dedicated semiconductor training schools to fortify its talent pipeline.

A Shield Taken Shape

Taiwan is home to two of the largest foundries in the world (TSMC and UMC) and accounts for 20% of global semiconductor manufacturing capacity. It has also distinguished itself as the dominant global producer of logic chips, manufacturing:

92% of the most advanced logic chips (<10nm),

28% of 10-22nm logic chips,

47% of 28-45nm logic chips, and

31% of >45nm logic chips

TSMC stands as one of only three global entities (the others being Samsung and Intel) capable of fabricating sub-7 nm logic chips. It is also the contract manufacturer for over half of the world’s semiconductors.

Though Korean competitors like Samsung can also produce the most advanced logic chips, they are integrated device manufacturers (IDMs) that both design and manufacture chips. Most of these Korean firms’ chipmaking capacities, therefore, go to internal production needs. Though IDMs like Samsung do offer foundry services to produce chips for third parties, external chip designers typically prefer to partner with pure-play foundries like TSMC that do not also compete with customers.

Bolstering the Shield

Before discussing Taiwan’s current semiconductor incentives policies, it helps to offer a Taiwanese Government 101 overview. As Taiwan’s principal administrative body, the Executive Yuan, assumes the mantle of law implementation. Laws must first be enacted by the Legislative Yuan, promulgated by Taiwan’s chief executive, and authenticated by the premier. Relevant to this article, the Executive Yuan oversees the Ministry of Economic Affairs, the Ministry of Education, and the National Science and Technology Council.

Taiwan’s equivalent of the US CHIPS and Science Act is its January 2023 Statute for Industrial Innovation. This law introduces massive tax incentives aimed at enticing semiconductor manufacturers to invest in cutting-edge production and research on the island.

Reacting to the global trend of tendering semiconductor subsidies, Taiwan’s program shows its determination to safeguard new chip technologies within its borders and to preserve its eminent “Sacred Mountain.”

These investments come at a critical time. Despite stringent regulations on technology flowing to mainland China, Taiwanese enterprises continue to build capacity in mainland China. Over 30% of Taiwanese companies’ annual foreign direct investment goes to the mainland, undermining the small island’s technological edge over the neighboring behemoth.

United States

Shortages and Declining Leadership

Previous Chip Capitols articles have explored the supply chain context inspiring the CHIPS and Science Act of 2022.

To summarize, the COVID-19 pandemic caused a severe chip shortage in the US due to unpredictable demand spikes, especially in the automotive industry. A slew of natural disasters then exacerbated the US’s already tight supply for all sorts of chips. Notably, a February 2021 winter storm in Texas knocked out power for chip fabs across the state, including Samsung’s facilities in Austin.

Longer term, the US’s global share of chip manufacturing fell from 37% in 1990 to 12% in 2020. Most US memory chip companies exited the market in the 1980s due to rising competition from Japan. Meanwhile, Taiwan and South Korea formed a duopoly on the global supply of the most advanced logic chips at 92% and 8%, respectively. Of greatest concern to US policymakers, mainland China’s share of global manufacturing has steadily risen from 3% in 2000 to 15% in 2020.

On the design side, the US still leads in developing chip architectures and EDA software tools, accounting for 46% of the global design market in 2020. Though this share has declined slightly from 50% in 2000, the US’s stronger position in this part of the chip industry has made design a lower priority for federal policymakers.

Micromanaged Hole Plugging

Faced with foreign subsidies threatening to degrade their chip industry’s leadership, US policymakers took a different tact than their Taiwanese counterparts.

First, while Taiwanese policymakers do not target their incentives to specific chip segments, American policymakers insist that federal subsidies bolster the weaker parts of the US semiconductor supply chain.

In its September 2022 strategy document, the Commerce Department pledged to restore the US’s global share in manufacturing advanced logic and memory chips. This decision heeds Congress’s singular focus on bolstering the weak parts of US chip supply chains, an emphasis lawmakers demonstrated by declining the semiconductor industry’s request that the CHIPS Act also subsidize semiconductor design. Not seeing a short-term or long-term crisis in American semiconductor design leadership, lawmakers were not willing to meddle further with the free market.

Second, while Taiwanese policymakers rely almost exclusively on tax credits, American policymakers prefer to keep control over subsidy recipients through grants.

In the formative stages of the CHIPS Act, many companies advocated for a greater emphasis on tax credits than grants because companies can claim tax credits automatically. In contrast, the version of the CHIPS Act that ultimately passed used grants as its primary tool. Grants involve application processes, through which companies must demonstrate how their projects align with the government’s policy goals.

Third, while Taiwanese lawmakers granted the Ministry of Economic Affairs wide discretion in administering subsidies, US lawmakers placed multiple restrictions on how the Department of Commerce could dole out CHIPS grants.

Congress engrained restrictions in the CHIPS and Science Act for a wide range of policy goals. These include: preventing CHIPS funds from offsetting expansions in China, limiting stock buybacks, forcing chipmakers to share their long-term business plans with the government, and requiring corporate childcare services.

Chip Incentives

Taiwan’s Tax Tango

Tax incentives emerge as Taiwan’s primary pillar of support to its chip industry. Grants from the National Development Fund amount to only a few hundred million USD; in contrast, grants are the US’s policy tool of choice.

Basic R&D Tax Credit (Article 10) — This incentive allows companies to deduct 15% of annual R&D expenditures or 30% of their annual income tax, whichever is less. Companies may alternatively choose to amortize (spread out) their credit as 10% of the first year’s R&D expenditures for each of three years.

Higher R&D Tax Credit (Article 10-2) — Recognizing the need for cutting-edge innovation, this provision offers additional benefits to domestic companies that MOEA determines hold a key position in the international supply chain. Companies can deduct 25% of annual R&D expenditures or 30% of their annual income tax, whichever is less.

Capital Expenditure (CapEx) Tax Credit (Article 10-1) — This incentive allows companies to deduct 5% of annual capex expenditures or 30% of their annual income tax, whichever is less. Companies may alternatively choose to amortize (spread out) their credit as 3% of the first year’s capex expenditures for each of three years.

Own-IP Revenue Tax Credit (Article 12-1) — This provision stimulates the export of Taiwanese IP. Companies that license their IP to foreign customers can deduct 200% of their R&D expenditures or the revenue from IP sold abroad, whichever is less. Companies can choose this credit or the capex tax credit under Article 10, but not both.

Tax-Free Treatment of Corporate Shared Received as Payment for Academia IP (Article 12-2) — This unique initiative aims at bridging academia and industry. It applies when a domestic academic or research institution assigns or licenses its IP to a company, receives shares in return, and subsequently distributes these shares to the IP creator. The IP creator may opt to exclude these new shares from her or his taxable income, resulting in an indirect government subsidy of the creator’s work.

Partial-Tax Free Income of Share-Based Compensation (Indirect Subsidization of Labor) (Article 19-1) — This provision also indirectly subsidizes labor costs by allowing employees who receive stock-based compensation to exclude up to NT$5 million ($162,657 USD) worth of acquired shares from their annual taxable income.

Other Provisions

As mentioned earlier, Taiwan has implemented rigorous regulations concerning outbound high-tech investments to mainland China. This is part of its commitment to safeguard leadership in the chip industry and preserve the “Sacred Mountain” that enables it to pursue greater autonomy.

International Collaboration (Article 21) — Central governing bodies are capable of extending support and guidance for industries aiming to undertake overseas investments or engage in global technological collaborations.

Overseas Investment Authorization (Outbound Investment Constraints) (Article 22) — Corporations intending to make overseas investments are obliged to secure approval or report to the central competent authority, contingent upon the scale of the investment.

America’s Grant Scalpel

Congress and the Department of Commerce sought to ensure federal subsidies plug holes in the semiconductor supply chain, keep government control over where taxpayer dollars flow, and achieve tangential policy goals relating to national security and inclusivity.

To secure America’s semiconductor supply chains, both legislative text and administrative implementation plans lay out where funds will flow.

As the most acute crisis, lawmakers wanted to ensure a sufficient amount of the $39 billion in CHIPS manufacturing funds would secure automakers’ access to chips. A bipartisan letter by members of Congress and governors from states with significant automobile industries urged funding for the CHIPS Act to prevent car production from stalling and causing mass layoffs. This concern grew so acute that lawmakers set aside $2 billion of the CHIPS Act’s funding specifically for fabs producing the older generation (mature node) semiconductors used in vehicles.

To guide the distribution of the remaining $37 billion in CHIPS grants, the Commerce Department issued a strategy document laying out the following goals. Federal subsidies would help establish:

Two leading-edge logic fabs to produce processors (CPUs and GPUs),

An unspecified number of high-volume leading-edge DRAM (memory) fabs to produce chips for PCs and servers,

“Multiple” high-volume advanced packaging facilities to help US fabs to finalize semiconductors for sale to device manufacturers, and

Sufficient mature node manufacturing capacity to meet the US’s economic and national security needs (this requirement may or may not require funds beyond the $2 billion mature node set-aside).

The Commerce strategy explains that meeting its advanced chip manufacturing goal will suck up “approximately three quarters of the CHIPS incentives funding under Section 9902, or approximately $28 billion.”

To maintain government control over the flow of subsidies, the largest incentive tool Congress approved was a grant mechanism.

Most of the CHIPS and Science Act’s support for the semiconductor industry comes via grants, providing US policymakers maximal control over the types of activity they incentivize. Commerce can scrutinize applicants’ proposed budgets to ensure the government only spends the minimum amount of public funds needed to incentivize domestic chip expansion that would not otherwise occur.

Though the CHIPS and Science Act does offer tax credits, the total $20 billion projected value of these credits is half the cost of the CHIPS manufacturing grants. Unlike the Commerce Secretary’s complete control over how she disperses manufacturing grants, the Treasury Secretary has limited discretion over the activities receiving tax credits beyond setting limited qualification criteria.

To reach political consensus on the biggest subsidy package for a single industry in years, Democrats and Republicans in Congress engrained tangential policy requirements into the CHIPS and Science Act.

Fearing that companies would simply use chip grants to offset expansions in China, Congress required that companies receiving CHIPS grants not expand capacity in China for ten years. Chip Capitols has discussed Commerce’s planned implementation of this requirement in depth.

The legislation also included stringent requirements for semiconductors companies that receive manufacturing subsidies, and it included optional further requirements for Commerce officials to consider including. Under the Commerce Department’s most recent implementation of these tangential requirements, companies must:

Not repurchase stock or issue dividends using CHIPS grants;

Provide childcare services for both the construction workers and permanent employees of their facilities;

Share with the US government any revenue that exceeds the grant recipient’s projections by an agreed-upon threshold; and

Submit to broad reporting requirements for the US government to ensure compliance with grant criteria.

Conclusion

Having birthed its national champions through public investment, Taiwanese policymakers trust the semiconductor industry to use subsidies without heavy-handed restrictions. Despite domestic political differences, Taiwanese lawmakers also seem to trust the executive branch to implement the island’s incentives with wide discretion.

Preserving its technological leadership is vital for Taiwan’s economic prosperity, as well as its pursuit of greater autonomy. The island faces a mainland that seeks to recruit talent away from Taiwan’s cutting-edge chipmakers, while nursing the Chinese Communist Party’s long-held aspiration for cross-Strait unification.

Most major markets have now passed their chip incentives, but no two governments’ packages look the same. Policymakers around the world design semiconductor subsidies in line with their regions’ unique conditions and goals. Chip Capitols has highlighted the distinctiveness of these programs in articles comparing US-China chip subsidies, US-EU chip subsidies, US-Korea chip subsidies, and now US-Taiwan chip subsidies.

We will conclude this marquée comparison article series soon with chip-policy coverage of the last major semiconductor producer: Japan.

Good work! Thanks.