My latest report in the Slovak think tank GLOBSEC builds off a report I wrote last year for the French Institute for International Relations (Ifri). Last year, I wrote in an Ifri report that China’s leading chipmaker, SMIC, is increasingly focused on dominating the domestic PRC market. From 2017 to 2023, SMIC’s share of sales to domestic customers increased steadily from 47% to over 80%. This year in my GLOBSEC article, I discuss the consequences of this dominance on European firms’ R&D budgets as they are crowded out of the PRC market.

An executive summary is copied below, and the full report is available for free here.

Executive Summary

Recent announcements by Chinese automakers that they will launch cars powered entirely by domestically produced chips mark another step in the gradual erosion of a historically vital market for European chipmakers. The European Union now faces pressure from China on two fronts.

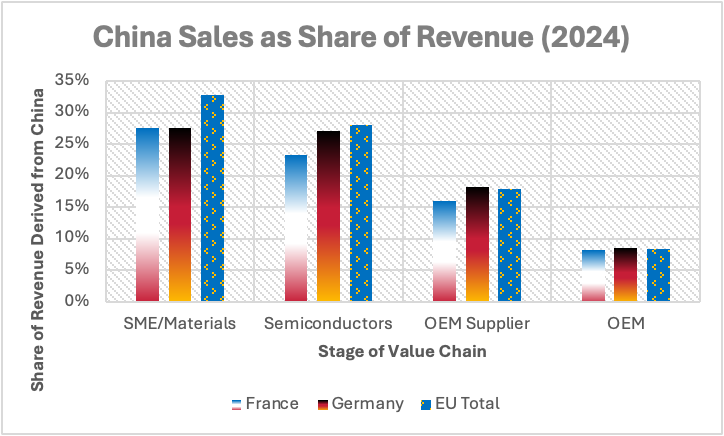

First, China’s accelerated drive for self-sufficiency in mature-node chip production is steadily pushing European suppliers out of a key market. Second, Chinese original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) are gaining ground in downstream industries, especially electric vehicles, where European firms are being displaced. These trends threaten not only the commercial outlook for Europe’s leading semiconductor companies but also the innovation capacity of the wider value chains they support.

Unlike the highly specialized ecosystems of the United States or Taiwan, Europe’s semiconductor value chain is relatively evenly spread across and downstream segments, from materials suppliers and equipment manufacturers to integrated device makers (IDMs) and OEMs. But as European chipmakers lose access to Chinese customers and face weakening demand from their own OEMs at home, their ability to sustain investment in research and development (R&D) is at risk.

Trade policy could, in principle, address the impact of Chinese state support. Yet divisions among EU member states make trade policy a difficult tool to use. Even if consensus remains out of reach, the EU and its member states can still act through domestic policies that safeguard firms’ ability to invest in R&D. To do so, while remaining compliant with EU state-aid rules, policymakers can use two levers:

Reinforce national public–private partnerships (PPPs) that anchor upstream R&D. Flagship institutions such as CEA-Leti and Fraunhofer should receive increased funding, coordinated with national industrial priorities. Additional public resources should target downstream applications in carbon efficiency and defence, which would also qualify under the revised public procurement policies described below.

Expand public procurement policies to create stable domestic demand for European chips. While the EU remains bound by its WTO commitments to treat foreign and domestic suppliers equally, Brussels can build on member states’ readiness to use exemptions in climate and defence. Procurement rules that factor in carbon efficiency can give European chipmakers an advantage, since their strengths lie in production and compute efficiency.

By aligning public funding with the needs of upstream players and using procurement to encourage downstream innovation, European policymakers can reduce the risks of global fragmentation and strengthen the resilience of Europe’s semiconductor value chains.