China’s SME Industrial Policy in 10 Charts

Equity Investments: Billions of Dollars, and Pandemic Sensitive

How much money is the Chinese government spending on chipmaking equipment… total?

Many studies over the past half-decade, including here on Chip Capitols, have tried to figure out how public funds flow from the various organs of the Chinese government to the semiconductor sector. However, the use of conservative methodologies has prevented scholars from bringing forth numbers for the entire ecosystem. The two standard approaches are:

Policy Announcement Hunting: China-watching platforms have tried compiling announcements of new semiconductor incentive schemes by China’s central and local governments (see Chip Capitols here on local government programs and here on central government tax subsidies). These program compilations help explain what sorts of policy tools the Chinese government deploys, but they cannot provide even a ballpark number for the total amount of RMB spent, because the Chinese government does not have transparency standards for public expenditures in the way the U.S. does.

Public Company Calculating: The OECD’s seminal 2019 report on market distortions in the semiconductor industry examined the subsidies that governments around the world, including China, gave to their champions. However, the study limited itself to 21 publicly listed firms because private companies do not have annual financial filings from which they could pull statistics on state investments and subsidies. This approach offers great accuracy, but it only captures a small slice of the Chinese public investment pie.

I set out to compile as comprehensive data as possible on Chinese equity investments, subsidy grants, and tax credits for the country's key semiconductor manufacturing equipment (SME) companies — regardless of whether they are public or private. This challenge required estimation based on the limited public statistics available for private companies, but it has allowed me to amass a treasure trove of charts about the Chinese SME sector.

Estimation is critical for reaching conclusions about the macro-state of upstream Chinese chipmaking equipment firms. The SME sector is small — relatively few firms are publicly listed, and some of the most important firms, like Shanghai Micro Electronics Equipment (上海微电子) (China’s only lithography firm), are notably absent from the public listing. Some of my conclusions may be proven wrong as I (or scholars more resourceful than me) develop more accurate methods of estimation; as more Chinese SME firms go public and their financial details become available, I will invariably need to revise these findings.

Nonetheless, the world deserves a first (if fuzzy) glance at the totality of China’s industrial policy for chipmaking equipment. Every week over the next three months, I will release a new chart about Chinese government support for SME firms through (1) equity investments, (2) subsidy grants, and (3) tax credits. Today, we look at equity investments.

Billions of Dollars, and Pandemic Sensitive

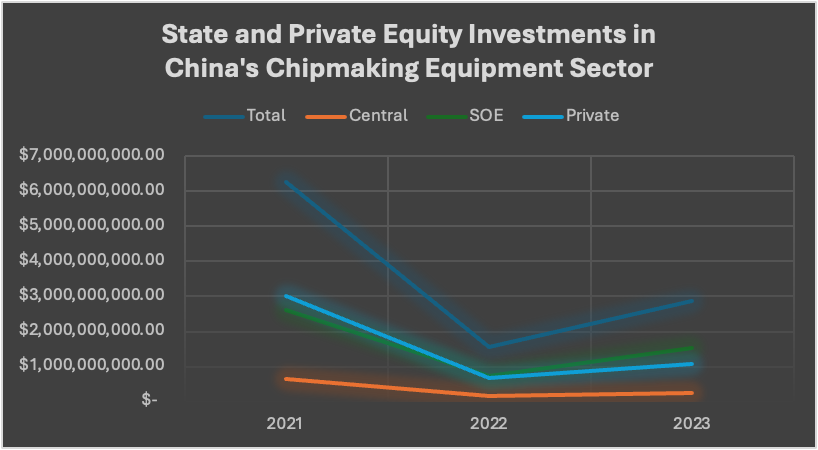

China’s investment in SME firms peaked in 2021 at $6.27 billion (a figure that includes investments by the central government, state-owned enterprises (SOEs), and private entities). Investment then fell to a trough of $1.57 billion in 2022 during the height of China’s COVID-19 pandemic. By 2023, investment rebounded to $2.86 billion — less than half of the 2021 figure.

Although COVID-19 first spread in China in late 2019, stringent lockdown policies kept the country functioning mostly as normal until stronger strains forced policymakers to adopt a “Dynamic Zero-COVID” policy in 2022 that wreaked havoc on the country’s economy. (Your author first landed in China at the height of the Zero-COVID era in fall 2022 and remembers getting his nose swabbed every day.)

Around this time, local governments poured inordinate amounts of money into COVID testing programs and quarantine hotels, leaving the localities strapped for cash more broadly. The sharp dip in semiconductor investments in 2022 likely reflects across-the-board belt tightening during that difficult year. This chart only categorizes investors into SME firms as those of (1) the central government (namely the Big Funds run as independent corporations with the Finance Ministry as lead investor), (2) SOEs (including state-owned banks), and (3) private (including all foreign) investors. As a result, the chart cannot isolate investments from local governments to see if the decline was also due to non-COVID-related trends in 2022. However, given the interlocking ownership by local governments and the central government of the largest SOEs, it is likely that the decline in SOE investments from $2.61 billion in 2021 to $0.73 billion in 2022 reflects local governments’ COVID-induced financial constraints.

It is less likely that the decline in central government investments from $0.65 billion in 2021 to $0.16 billion in 2022 was due to COVID. The only mechanism of central government investment this research identified was the (at the time) two iterations of China’s Big Fund (大基金). As a reminder for newer Chip Capitols readers:

The first phase of the "Big Fund" raised 139 billion yuan ($20 billion) and invested in 23 companies across the chip industry from September 2014 to May 2018. There were 16 shareholders in the first phase of the Big Fund, among which the Ministry of Finance accounted for the largest share at 36.47%. Among projects receiving investment, chip manufacturing accounted for 67%, chip design 17%, packaging and testing 10%, and SMEs/materials 6%.

The Big Fund’s second phase was established in October 2019, aiming to raise 201 billion yuan ($29 billion). Besides government and SOE contributors, some private companies also joined the round, but the Ministry of Finance still accounted for the largest share at 11.02%. As of March 2022, the second phase fund had announced 79 billion yuan ($11 billion) in investments in 38 companies, with 10% for design, 2.6% for packaging and testing, and 10% for equipment/materials .

Because the Big Fund investments were arranged in advance, it is more likely that the dip in investments in 2022 was coincidental, rather than due to COVID-induced restraint.

What’s Next

In the coming weeks, we will dive deeper into China’s equity investments to see whether investments by the central government and SOEs served as effective signals to private investors, or whether public and private actors invested independently. Grand assumptions about the Chinese Communist Party’s ability to centrally coordinate its industrial policy are at stake in that future chart.

We will also soon begin releasing charts on China’s other major tools for supporting its SME industry: grants and tax credits. These subsidy tools shine light on both the sectors of the chip industry that China prioritizes the most as well as on how different policy tools are more or less reactive to shifting domestic political climates in the PRC.

Stay tuned!

Methodology

The following companies were analyzed for this article on equity investments. The scope of firms selected comprises (1) all of those known to have received investments from either of the first two Big Funds, as well as (2) those with the most advanced domestic technology in China in the following equipment areas: lithography, etching, deposition, implantation, epitaxy, and metrology.

Despite your author’s greatest efforts, I could not collect enough data about the not-publicly listed Shanghai Micro Electronics Equipment (SMEE) to speak confidently about its equity investments; however, subsequent charts about China’s subsidy grants and tax credits will include estimations of how SMEE benefited from those policy tools.

Firms analyzed:

中微公司|Advanced Micro-Fabrication Equipment Inc. China

北方华创|NAURA Technology Group Co., Ltd.

拓荆科技|Piotech Inc.

天水华天|Tianshui Huatian Technology Co.,Ltd.

长川科技|Hangzhou Changchuan Technology Co., Ltd.

芯源微|KINGSEMI Co., Ltd.

盛美上海|ACM Research (Shanghai) , Inc.

中科飞测|Skyverse Technology Co., Ltd.

华峰测控|Beijing Huafeng Test and Control Technology Co., Ltd.

华海清科|Hwatsing Technology Co., Ltd.

新益昌|Shenzhen Xinyichang Technology Co., Ltd.

屹唐半导体|Beijing E-Town Semiconductor Technology Co., Ltd.

北京烁科中科信|Beijing Zhongkexin Electronics Equipment Co., Ltd.

凯世通|Shanghai Kingstone Semiconductor Corp

浙江镨芯(万业企业)|Zhejiang Praseodymium Core Electronic Technology Co., Ltd.

至微半导体|Not certain about English name: Zhiwei Semiconductor

沛顿存储|Payton Technology(Shenzhen) Co., Ltd.

东科半导体|Dongke Semiconductor Wuxi Co., Ltd.

精测半导体|Shanghai Precision Measurement Semiconductor Technology,Inc.

睿励科学仪器(上海)有限公司|Ruili Scientific Instruments (Shanghai) Co., Ltd.

东方晶源|Dongfang Jingyuan Electron Limited

合顿科技|Hefei Payton Storage Technology Co., Ltd.

For public companies on the list, I identified their top ten equity holders (central government, SOEs, and private) per quarter from Wind (万得), a site similar to Bloomberg that aggregates financial data on public companies. I then calculated each investor’s quarterly change in position to determine how many of each company’s stocks changed hands per quarter. Then I calculated how many new stocks each firm issued per year to determine how much new liquidity these investors provided each firm through their stock purchases. That “new liquidity” is the measure of support via equity investments.

For private companies on the list, I found public reporting on their investing rounds and categorized investors into the same three buckets (central government, SOEs, and private) as for public firms.

For any questions about methodology or to propose further research, please contact me at arrian.chipcapitols@gmail.com.

Many thanks for your work. Much appreciated.